Her Story: Dorthea Lange

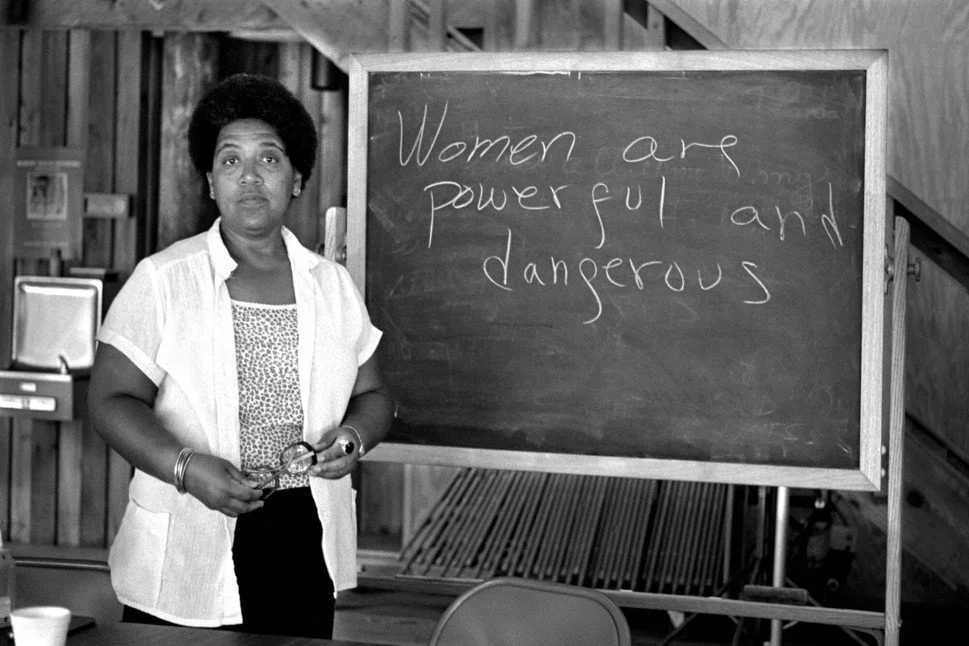

Photo from MoMA.

Peyton Impola

Perhaps every student who has ever studied the Great Depression is familiar with the image Migrant Mother. The photograph of a worn down mother, beat down by the intense poverty of the Great Depression has left an impact on millions. It highlights the desperation and pain families nationwide experienced in the face of widespread poverty. However, what people may not realize is that the photographer behind this photograph was more than an artist–she was an activist and fighter for social change. Dorthea Lange was a revolutionary photographer, and the long lasting impact her images have left on American society and culture cannot be overstated.

Lange’s childhood was not an easy one. At the age of seven, she contracted Polio, leaving her with a withered right leg and twisted foot. Her disability made it difficult for her to walk. However, these hardships didn’t keep Lange down–she was a woman with an incredible sense of ambition, especially at a time in which women were looked down upon for ambition.

By the time Lange graduated from high school, she had yet to even own a camera. This didn’t stop her from deciding to pursue a career in photography. At Columbia University, Lange studied under Clarence Hudson White–a very notable photographer for his time. Her career continued to blossom, and she gained several very prestigious internships. In 1918, Lange left New York and settled in San Francisco, where she found a wealthy investor to aid her in establishing a portrait studio. In 1920, Lange married another photographer, whom she had two children with. For the next fifteen years, Lange’s studio business supported her family, and her studio mostly focused on photographing the wealthy elite of San Francisco.

Everything changed when the Great Depression struck. Lange decided to move her camera out of the studio and onto the streets. She wanted to document the hardship and poverty that the American people were burdened with. It is important to note that Lange did not classify these photographs as “art” but rather as tools of social justice. Her photographs of crowds standing in lines for soup kitchens, or the makeshift homes that the impoverished and unemployed huddled in caught the attention of the media. It was this attention that earned Lange a job with the federal Resettlement Administration. While with the Resettlement Administration, Lange traveled through the California coast and Midwest, documenting rural poverty and its effects. The pictures she took were distributed to newspapers across the nation, bringing attention to those often forgotten by the rest of society–like sharecroppers, migrant workers, or displaced families.

The most notable of Lange’s images is Migrant Mother, which depicts a desperate mother crushed by the burden of poverty. The woman in the photograph–Florence Owens Thompson–was living in a camp, attempting to feed her children with dead birds and frozen vegetables in the frost bitten fields. After taking Thompson’s photo, Lange managed to get in contact with federal authorities, who then rushed to the camp to try and prevent the inhabitants from starving to death.

Lange’s Depression era images were her most notable, and had a profound impact on society. However, Lange’s work did not stop there. In 1941, she was offered a very prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship for her achievements in photography. Lange rejected the offer, and, in the wake of Pearl Harbor, followed an assignment by the War Relocation Authority to document the internment of Japanese-Americans. Lange strongly opposed this policy, and the images she took were very critical, depicting the harsh conditions, and the waiting and anxiety that the disruption caused. Though the government suppressed these images during the war, they are now available, and serve as a haunting reminder of one of the most flagrant violations of civil liberties committed by the US government.

Lange continued to chase her passions for the rest of her life. In the decade following World War II, she co-founded a photography magazine named Aperture. Life hired her to do several photo pieces in the years that followed. Sadly, in the last decade of her life, Lange’s health began to decline. In 1965, Dorthea Lange died of esophageal cancer. Three months after her death, the Museum of Modern Art mounted a retrospective of her work, which Lange had helped curate. It was MOMA’s first retrospective of the works of a female photographer. In 1984, Lange was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum, and in 2003 she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Her legacy is undoubtedly one of ambition and drive. It is the legacy of a woman who fought for those society forgot, and fought to bring about social justice and change with her work. Our nation owes Dorthea Lange a debt of gratitude for protecting the underdogs in a time when it was so easy to fall through the cracks and disappear.

Sources

Dorthea Lange: Drawing Beauty out of Desolation

Introduction-Dorthea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” in the Farm Security Administration Collection

Other Works in This Series

Check Out These Other Feminist Features

Patsy Mink and the Road to Title IX

Bell Hooks: Empowering Marginalized Women

Edith Wilson: Secret President

Mary Anning: Mother of Dinosaurs