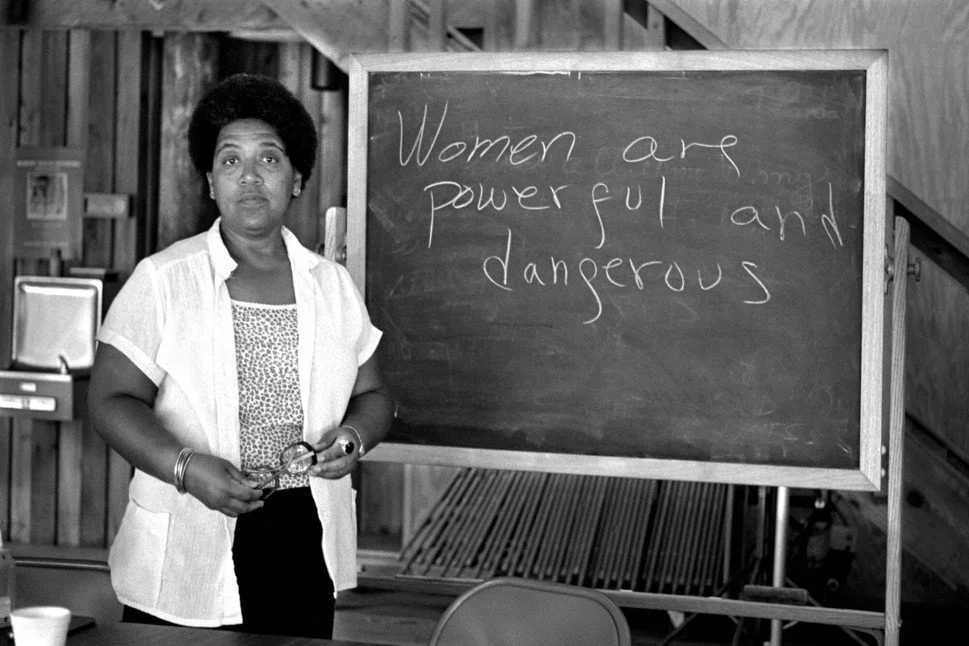

Audre Lorde: Powerful and Dangerous

Photo from Poetry Foundation.

Peyton Impola

“ Do not remember me

as disaster

nor as the keeper of secrets

I am a fellow rider in the cattle cars

watching

you move slowly out of my bed

saying we cannot waste time

only ourselves.

”

Those who feel like outsiders can often produce some of the most beautiful works of art the world has to offer. No one better exemplifies this than Audre Lorde. The poet felt like an outcast for a large portion of her life–facing distance even from her mother. Despite these challenges, the poems Lorde penned are a beautiful and eloquent look into the life of a strong, lesbian, Black woman who had to live through an era in which many aspects of her identity were marginalized and oppressed.

In February of 1934, Lorde was born to Caribbean immigrants. Her father was originally from Barbados, and her mother hailed from Grenada. The young family settled in Harlem, and Lorde, the youngest of the three daughters, grew up hearing her mother tell stories of the West Indies. At the age of four, Lorde learned how to read and write–both of which she was taught by her mother. By the eighth grade, Lorde had written her first poem.

Though she was born Audrey Geraldine Lorde, the poet eventually dropped the “y” from her name. In her book Zame: A New Spelling of My Name, Lorde explains that she favored the “artistic symmetry” of both her first and last name ending in the letter “e.”

Lorde’s relationship with her parents was complex and tumultuous. Both her mother and father were dedicated to maintaining their real estate business in the midst of the Great Depression, which meant that they had very little time to spend with their children. The time the family did spend together was stifled by emotional distance. Colorism played a huge role in the family’s dynamic–even before Lorde was born. Lorde’s father was disliked by her mother’s family due to the darkness of his skin. Lorde’s mother harbored suspicion and distrust for those with skin darker than her own–including her daughter.

Poetry was a gift for a young Lorde, who had issues with communication. She describes herself as “thinking in poetry.” The young woman had a deep appreciation for the power of poetic expression. She took it upon herself to memorize a myriad of poems, and would use experts as responses in conversation. Around age twelve, Lorde began to write her own poems, and to befriend others that considered themselves societal outcasts.

Because she was raised Catholic, Lorde attended parochial schools before transferring to Hunter College High School–an institution for intellectually gifted students. While attending the school, Lorde published her first poem in Seventeen, after the poem was rejected from Hunter’s literary magazine for its “inappropriate” contents. Also during this time, Lorde participated in poetry workshops that the Harlem Writers Guild sponsored. However, Lorde still felt like an outcast, even in the Guild.

Lorde’s feelings of isolation stemmed from many things. Her relationship with her mother and the colorism that she felt in her household put her on the outs with her parents from an early age. Lorde’s identity as a lesbian woman, and a woman of color during a time in which both groups were severely marginalized also increased her feelings of loneliness and isolation.

After graduating high school, Lorde spent a highly influential year at the National University of Mexico in 1954. This period of time offered her affirmation and clarity on her identity. After this experience, she confirmed her identity as both a lesbian and a poet. After returning to New York, Lorde attended Hunter College, graduating in 1959. While a student at Hunter, she worked as a librarian and continued her writing. During this time, Lorde also became active in the gay community of Greenwich Village. After graduation, Lorde continued her education at Columbia University, earning a master’s degree in library science.

By 1968, Lorde was a writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi. Her time at this university was just as impactful as the year she spent at the National University of Mexico. Lorde led workshops with young, Black, undergraduate students, most of whom were eager to discuss and involve themselves in the ongoing Civil Rights Movement. Her book of poems Cables to Rage stemmed from her time at Tougaloo.

Beginning in 1972, Lorde made her home in Staten Island. Along with teaching and writing, she also co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Table Press, an activist feminist publication. These years saw the poet becoming deeply involved in social justice. She was active in providing aid to sexual abuse survivors, Black women affected by apartheid, and the LGBTQ+ community. In 1985, Lorde was a part of a delegation of Black women writers who were invited to Cuba. The coalition met with two female Cuban writers, and discussed whether or not the revolution in Cuba had improved the status of Black citizens and members of the gay community.

Lorde continued to write and publish throughout her career. Her works involved ideas on racism, homophobia, chronic illness, and feminism. She published many of her works on the basis of the “theory of difference.” This stated that binary opposition between men and women is too simplistic, and that though feminists tried to portray womanhood as a unified whole, there were actually many subdivisions within that category. Lorde wanted these differences–like race, class, and sexuality–acknowledged and not judged. Today, feminists know the “theory of differences” as intersectionality. The poet made it her goal throughout her career to tackle racism within the feminist movement, which led many white feminists to attack Lorde. However, Lorde’s work in the field of feminism is still taught and used today. Her impact on feminist ideology cannot be overstated.

Lorde’s adult personal life was complicated. In 1962, she married Edwin Rollins–a white, gay man. After having two children, the two divorced in 1970. During her time in Mississippi in 1968, Lorde met Frances Clayton–a fellow lesbian and professor of psychology. The two were romantic partners for 21 years. In 1978 Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer. In 1981, following the diagnosis, Lorde met Dr. Gloria Joseph, who would become her life partner. Joseph was a self identified “radical, Black, feminist, lesbian.”

Despite undergoing a mastectomy, six years after her initial diagnosis, Lorde discovered that her cancer had metastasized in her liver. The effects of these diagnoses pushed Lorde to publish The Cancer Journals which was critically acclaimed. On November 17, 1992, Lorde died of cancer at the age of 58.

Before her death, Lorde took part in an African naming ceremony. The name she chose was Gamba Adisa, meaning warrior: she who makes her meaning known. There is no better name to fit such a trailblazing woman. Despite the fact that the time in which she lived was dangerous and oppressive to both women of color and gay women, Lorde wore her identity with pride. She was strong and independent, and she used poetry to express herself in ways that normal words couldn’t. Lorde represents power for women who look and feel the way she did. With her death, marginalized communities lost one of their fiercest and most dangerous warriors.

Sources

Audre Lorde | National Museum of African American History and Culture

Audre Lorde | Poetry Foundation

Other Works in This Series

Patsy Mink and the Road to Title XI

Bell Hooks: Empowering Marginalized Women

Edith Wilson: Secret President

Mary Anning: Mother of Dinosaurs